In recent years, there have been more accusations of cheating in chess, due in part to the proliferation of smart phones and pocket computers. Now, a professor in Buffalo claims he’s found a way root it out.

But mathematician Kenneth Regan’s methods aren’t accepted by everyone.

Toiletgate

Every chess player has his or her own style. Russian Vladimir Kramnik likes to take bathroom breaks during matches. That got him in some trouble five years ago.

“There was this horrible scandal in October 2006,” says Regan, of the University at Buffalo’s department of computer science and engineering. “An accusation of cheating at the world championship match - that’s at the very highest level.”

Kramnik won the match in a dramatic fashion, coming back against tall odds. But he was accused of using a computer while in the bathroom. The scandal became known as “Toiletgate.”

The Russian forcefully denied the allegations, but how could he prove it?

Regan says a cloud of suspicion descended on the Grand Master after his final moves were revealed to match the suggestions of two widely-used computer chess programs, Fritz and Rybka.

“Of those 32 moves, 29 of them [matched] Fritz, 30 of them matched Rybka. Those are both 90 percent,” Regan says. “So to the layperson that sounds that obviously that [Kramnik] must be having high coincidence with the computer.”

But many of Kramnik’s moves were forced, meaning there was no other move he could make to either stay in the game or not lose game pieces. Regan ran a sophisticated statistical analysis of Kramnik’s optional moves that showed he simply chose the right moves, while his opponent made questionable decisions.

“So in a sense it statistically exonerates Kramnik,” says Regan. “It explains his high coincidence in the latter stage of that game.”

200,000 chess games

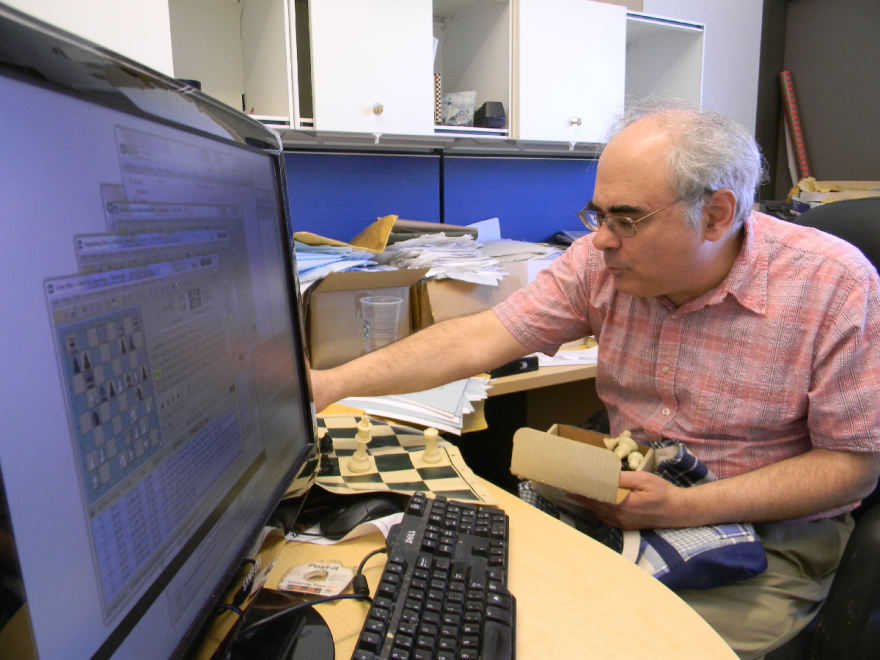

Regan didn’t stop with that match. Sitting at a computer in his University at Buffalo office, four simultaneous games are playing out in front of him.

“This is in fact a game from the 1937 world championship match where Alexander Alekhine regained his title,” Regan says.

The game is just one of the more than 200,000 now in his database. As the games play out, Regan records the computer’s “opinion” of how the players perform.

“So here the computer is saying [the white player’s] best move to push the King pawn forward, E6. A sacrifice that [Alekhine’s opponent] the Dutch player Max Euwe evidently didn’t notice,” he says.

The computer will eventually observe nearly all possible chess moves. From there, future matches can be analyzed and scrutinized.

But Regan admits his methods are not definitive. Skeptics say it raises the specter of cheating where there may be none. This controversy plays out on Internet message boards, which Regan checks often.

There’s also the charge that technology and deep statistical analysis strips the game of some of its soul.

Regan’s an avid chess player himself. He argues that the essence of the game - two people trying to outsmart each other - endures.

But he doesn’t admit that the game has changed “by the fact computers are better than we are.”