About 4 million gallons of water goes into a typical Marcellus Shale well during the fracking process. As much as 20% of what went in comes back out right away. That’s what’s known as flowback water.

Over the life of a producing well, more than a million gallons comes out, and after the initial flowback the rest is known as produced water.

In Pennsylvania, treating that water for metals and total dissolved solids and radioactive materials at public treatment plants has caused problems.

Hydrofracking for natural gas is on hold in New York while the Department of Health reviews its potential health impacts. If New York permits the controversial drilling technique, one of the obstacles is how to handle the huge amounts of wastewater produced by each fracked well.

In Pennsylvania, drillers are increasingly using private treatment plants as a way to deal with all that waste.

Tom Johnson, a hydrogeologist in Clifton Park, NY, says the challenges drillers faced brought the private companies in.

“Where there’s some profits to be made, obviously, somebody will come in and develop a business to meet the need that industry has,” says Johnson.

In the last few years, Williamsport, Pennsylvania has become a center for the drilling industry, including for private treatment plants.

The cheaper option is underground injection, the wastewater goes into the well untreated. But those are mostly found in Ohio, a long way from Northeast Pennsylvania.

According to Johnson, the lack of injection wells in Northeast Pennsylvania and New York can be overcome.

“If you hear characterizations that say this water can’t be treated, it’s kind of nonsensical because there’s a very, very large water treatment industry out there that treats wastewater on a daily basis,” says Johnson.

In Susquehanna, officials from Cabot Oil and Gas say the company recycles 100% of its wastewater and uses it to frack new wells. They’re spared the hardest step in purification because salty water can be reused for fracking.

At a temporary facility in Springville, Pennsylvania, Cabot’s wastewater moves through a series of tanks protected from the weather by plastic tarps and a floor of steel plates.

Mark Banyas supervises the plant for a treatment company called Chemtech Industries. He says the facility can handle multiple wells at once and it takes about 3 hours to go through the whole process.

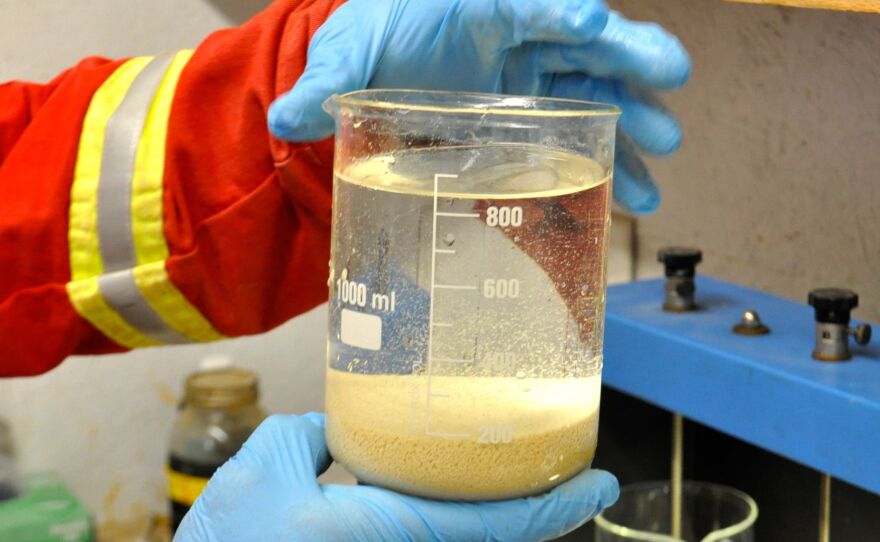

When the water comes in, it's muddy and obviously contaminated. Chemicals are added to separate the solids from the water and, in the end, and clear, salty water is left. The solid waste is then compressed into a clay-like bricks and sent to landfills.

Some companies also use mobile treatment technologies at well sites. Multiple wells are drilled at each well pad, so the water that comes back up from one can be treated and sent down another, or trucked to a site nearby.

A company in Long Island called Advanced Waste and Water Technologies uses an electric charge to fully treat wastewater.

Another called Filtersure uses a system with multiple filters to recycle it.

Brian Rahm of Cornell’s Water Research Institute says these sorts of systems are likely to be used in New York if hydrofracking moves here. And the water that can’t be recycled will probably be shipped to disposal plants in Pennsylvania.

“To truck the waste from Broome County down to Williamsport is probably not that big of a deal. I think they’ll probably use that capacity,” says Rahm.

He says that the most important thing isn’t whether or not wastewater can be treated. It’s whether the Department of Environmental Conservation can enforce the rules they’ve spent the last five years creating.

“That to me seems the biggest problem right now is not being quite sure how New York DEC is going to undertake all the things they say they’re going to undertake,” says Rahm.

According to Rahm, there needs to be a lot of drilling before water treatment plant operators, which need permits from the state and the federal government, start building new plants in New York.