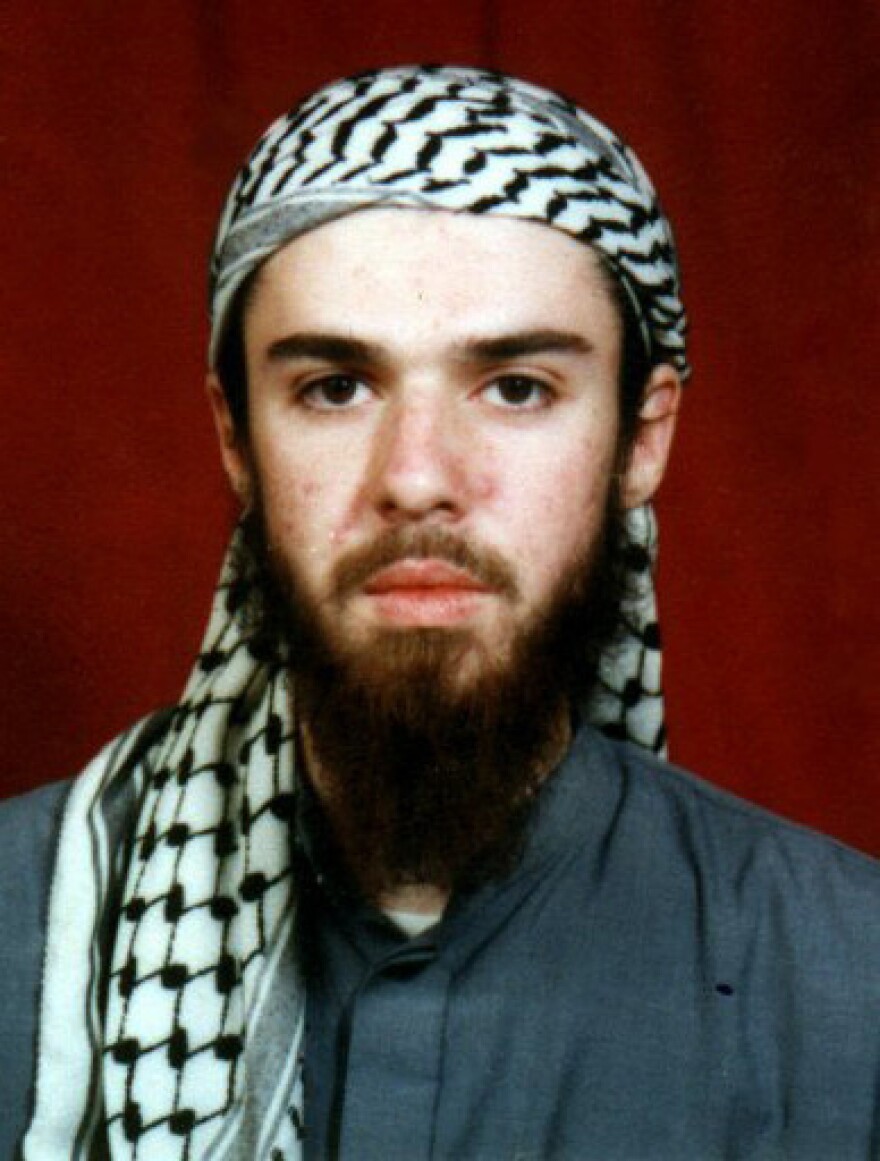

John Walker Lindh was a middle-class kid in Northern California who converted to Islam and went to travel the world. U.S. authorities eventually captured him in Afghanistan after Sept. 11, when he was allegedly fighting alongside the Taliban.

His story was the focus of a Law and Order episode, and a song called "John Walker's Blues" by Steve Earle.

For the past five years, Lindh has been living in a secret prison facility in Indiana with convicted terrorists, neo-Nazis and other inmates who get special monitoring.

On Monday, Lindh will come out of the shadows and into a federal courthouse in Indianapolis, as the plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

The devout Muslim wants to be able to pray together with his fellow inmates every day from inside the walls of his secret prison unit in Terre Haute, Ind.

"They can sit around and talk about politics or football or whatever philosophy," says Ken Falk, a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union who's representing Lindh. "The one thing they're not allowed to do is pray together for their daily prayers, which many Muslims believe is required or at least strongly preferred."

Falk says the prison system is stepping on the rights of those inmates to practice their faith under a federal law called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

The Bureau of Prisons didn't want to talk about the specifics of the case. But it argued in court papers that allowing inmates to pray together every day could pose a security threat and could ignite violence against Muslims by prisoners who follow other religions.

Prison officials add that Lindh has had some discipline problems. He got in trouble for making a call to prayer early in the morning. Next, he got cited for praying in a cell with other people. And in the third episode, the warden accused Lindh of being "insolent" after his family visits got cut short.

"Anyone would have reacted with anger to two terminations of visits with family members who are traveling two-thirds of the way across the country," says Falk, who contends that the other infractions didn't represent anything serious.

It's hard to know what goes on inside the secret prison facility where Lindh lives. It's known as a Communications Management Unit, or CMU, a place for prisoners who are restricted from contact with outsiders.

But Hal Turner gave us a glimpse. Turner is a former talk radio shock jock and paid informant who helped the FBI keep tabs on white supremacists. He was eventually convicted of making online threats against judges in what prosecutors called a "campaign of intimidation." He lived in that special unit in Indiana for over a year, until June.

"Overall, the CMU got along fine because we were all in the same boat," Turner said in a phone interview with NPR. "Regardless of ideology, regardless of whatever offense was allegedly committed, that was our home, and nobody likes violence and trouble at home."

Turner says he witnessed a couple of violent attacks inside the unit, even though it's filled with cameras and listening devices planted every 20 feet.

In one instance, he says, an elderly inmate "was hit in the head with the bristle end of a commercial sized push broom. The guy that hit him was a black Muslim, and they had some sort of dispute. And the Muslim picked up the bristle end of the broom and swung it like a baseball bat, splitting this man's head open."

Chris Burke, a spokesman for the federal prison system, told NPR in an email that "while we strive to prevent inmate violence at all of our institutions, in some cases even close supervision and monitoring of inmates does not prevent inmates from violating rules or committing new crimes."

Burke said authorities investigate any violence behind bars and refer cases for prosecution "when warranted."

In a companion CMU prison unit, in Marion, Ill., Muslim inmates went on a hunger strike this year. A posting on Facebook dedicated to the incident reports they were fighting interruptions during their prayer times, decisions to cancel religious classes and the refusal to provide special meals.

Turner said he doesn't have a strong opinion on religious freedom inside the prison system. He told NPR he's more bothered by leaking toilets, cockroaches as wide as a man's thumb, and blackened potatoes served to the inmates even though boxes of food were allegedly labeled "unfit for human consumption."

The prison spokesman said officials monitor pest control and food complaints.

Veterans of those CMUs say the way prison officials treat inmates there matters because, unlike inmates at Guantanamo Bay, people who live in those special U.S. prisons eventually go back home.

"You know, on the one hand the government claims that the people sent to that unit are extra-special dangerous and therefore need extra-special monitoring," said Turner, who's living in a halfway house in New Jersey while he transitions back home. "And then the government turns around and releases us back into society, abruptly."

John Walker Lindh has seven years to go.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.